Below is the transcript from the fireside chat titled “Measuring What Matters: From Conversations to Collective Impact” that took place on August 15, 2025. To access the Portuguese translation of the transcript, switch the language to Portuguese on the top right-hand corner.

Erin Simmons: Welcome to our Fireside Chat measuring what matters, from conversations to collective impact. I’m Erin Simmons, Chief Operating Officer at Imaginable Futures. I also lead our learning and impact work. I’m a white woman wearing a salmon colored dress with short blonde hair, and I’m joining you from my childhood home in California today.

We’re thrilled to have you all with us. Today’s conversation is particularly exciting because we’re pulling back the curtain on how we’ve been thinking about systems and impact, and the framework that we use to measure it and how to make it come to life. Across all of our work in Brazil, Kenya and the US, measuring systems change can be messy and complex, and what we’ve learned, though, is that the measurement process can also fuel learning, build trust and drive collective progress, especially when approached thoughtfully.

So today, we’ll explore how we at Imaginable Futures are reimagining what it means to measure what matters by placing learning, our values and humility at the center of our approach.

Before we get started, a word on accessibility: there are captions available in English to all participants. To turn those captions on, please click on the CC live transcript button at the bottom of your zoom window. Unfortunately, due to technical issues, we’re unable to provide live Portuguese translation and captioning today. However, we will be able to translate today’s event in the recording that will be shared in follow up. We’re very sorry for this inconvenience.

We’ll have some Q and A at the end. And if you have a question that you’d like to share with our panelists during this conversation, please put it in the Q and A box. With that, let me turn it over to my wonderful colleagues to introduce themselves as well.

Enyi Okebugwu: Thank you, Erin. Good afternoon, good morning, good evening, depending on where you all are joining in from today. My name is Enyi, like “anyone,” and I am a senior program manager at Imaginable Futures, and I help shepherd our learning journey in the US. For reference, I am an African American male wearing a purple t-shirt and gold rimmed glasses, and I have neck-length dreadlocks. My pronouns are he/him.

I’m a member of our learning core team, which is a cross-functional team, where learning facilitators from each program team come together to learn with and from each other, build new skills, explore new frameworks and identify when and how to engage in learning across the organization. Essentially our learning core team shepherds our learning and impact work across the organization. With that, I’ll pass it off to Nathalie.

Nathalie Zogbi: Thanks, Enyi. Hi everyone. My name is Nathalie, speaking to you all from São Paulo, Brazil. I am a white woman with brown hair wearing a blue t-shirt. I’m a program manager for our Brazil work. With that intro, let me turn it over to Jewlya to introduce herself, and then I’ll kick us off.

Jewlya Lynn: Hello, everyone. My name is Jewlya Lynn, and I’m an independent consultant. I’ve been focusing on supporting philanthropic efforts to influence complex systems and advance equity and justice, which is a big part of what I’m doing with Imaginable Futures. I’ve been involved during their framework development and implementation and supporting their learning practices. For reference, I’m a white woman. I’m wearing a black t-shirt. I have short brown hair and silver blue glasses, and my pronouns are she and her. I’ll pass the mic back to you, Nathalie.

Nathalie Zogbi: Thanks, Jewlya. To get us started, let me share a little bit about what drove us to develop this framework. A couple of years ago, I would say maybe four to five years ago, we were still using some impact related metrics that, as we began transitioning to more systems-aware strategies with a systems lens, we began feeling that those more traditional, quantifiable-based KPIs were falling short of really helping us to understand our work, the impact of our work, the impact of our partners’ work in the field.

For a while, right after beginning to realize that those metrics were really not serving us well, we swung the pendulum the other way. For a little bit of time we were actually absent of metrics. And so when we began implementing our strategies in Brazil, in the US and in Kenya that had a systems lens, we did begin wondering, like, what then can we use? Because also having an absence in trying to understand our work also wasn’t serving us well.

And so after the pendulum swinging that way, we decided that we needed to land somewhere in between the very hard KPIs and nothing that we had for a while. And this in-between is what we today call our systems and impact framework, where we try to have sort of a multi-layered approach that Erin will explain in a bit, to really try to capture our learnings from the field and from our work directly. So I’ll turn it over to you, Erin, to walk through the framework for us.

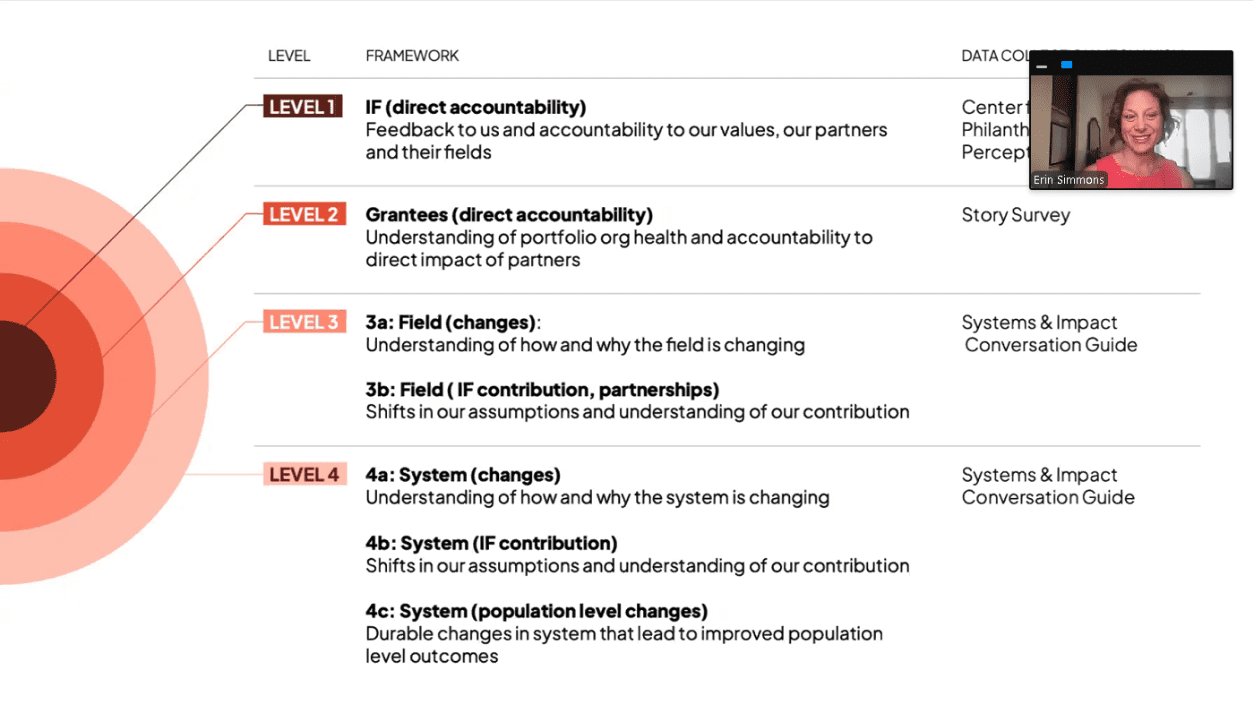

Erin Simmons: Thanks, Nathalie. So as Nathalie mentioned, our framework works across four interconnected levels, and they’re each designed to capture different dimensions of change and impact. When you start at the center, this is what we feel we’re most in control of as a funder and as a partner.

So level one focuses on our own organization, and that’s examining how we’re showing up. Are we living to our values? Are we being effective collaborators? And to measure this, we use the Center for Effective Philanthropy’s Grantee Perception Report primarily, every two to three years, which gives us that direct feedback from our partners on how they experience working with us. Of course, this is not the only place that we gather that kind of data.

Level two centers our grantees and their work. So moving out from the center, capturing the full spectrum of the good that they’re creating in the world, from direct service in their communities all the way up to systems level change. And for this level, we’ve developed a story survey that allows grantees to share narratives and stories about their impact in their own words, which gives us richer understanding of the diverse ways that they are creating that impact.

Levels three and four – that’s really about field and systems change, the broader transformations happening beyond individual organizations, the ways in which we’re fundamentally shaping, changing, contributing to the dynamics in the system. This is where we deployed our systems and impact conversation guide, which Jewlya will share a little bit more about in a moment. This conversation protocol enables us to have intentional, in-depth dialogs with partners, to understand both the changes that are occurring in the field and system, and to better grasp our own role in catalyzing those changes.

Of course, this is just where we ended up as an organization. Jewlya played an integral part in getting us here and perhaps most importantly, helping us to establish, first, our learning practice. But there are many ways for organizations to think about how to measure impact. Jewlya, I’d like to invite you into the dialog for practitioners wanting to evolve their measurement approaches. Where would you suggest that they start?

Jewlya Lynn: I’ll suggest where you don’t start, which is where we often do. So it’s easy when we’re starting to think about impact, to go straight to a theory of change, to say, what are the outcomes we want to advance? What are the facts we want to know about those outcomes? What’s the concrete information that will tell us that we’ve had impact? In a way, this is a bit of “what do we want to prove? What do we want to say we have been accountable for, and how we’ve driven change?”

The problem with that is, if you’re working in complex, dynamic systems, you’re centering your own understanding and your own work, but the system is a whole lot more than that, and it’s unpredictable, and there are many moving parts, and there’s so much going on that you can lean into. By centering your own work, you’re missing that bigger and really actionable picture.

So instead, we want to start with, how are we going to use this information? With whom, for what purpose? And then start to ask questions like, what’s going on in the system that we can’t see? What is the information we need to know? Where are we missing critical things that would change how we think about our work?

One of the things that we want to be challenging ourselves with when we start to develop a framework like this is, how are we going to avoid reinforcing what we already know and instead gathering and using information that integrates with our current knowledge, but often can challenge it as well? And so often this nuance here that I’m talking about is really understanding how and why and under what conditions the system is changing. So centering the system, not centering your strategies, and then finding your own impact in that larger story.

So Imaginable Futures did that. They already had a really strong learning practice in place before they moved to impact, so they were ready to be listening to these stories. And one of the really critical parts of that process, then at the beginning, was to say, what is our purpose of even doing impact measurement, and what are design principles that match who we are as an organization?

So one of those design principles – Imaginable Futures truly does emergent work, is regularly reassessing. Doesn’t have kind of big plans that you implement for three to five years and keep going on. And so for them, the design principle meant that this impact measurement had to offer them context and information to support adaptation, and had to do it in specific time frames and fairly rapidly when the teams were ready to use that information for adaptation.

The next part of the process: So you figured out, “Hey, this is why we’re using the data. When we want to use the data, the changes we’re going to drive, what we really care about here,” you also need to think about, well, what sort of tool helps us to learn these things?

So often we see organizations that have really concrete and specific outcome and output metrics. Maybe they’re collected through grantee surveys or reporting. They might know the number of people served, the activities implemented, or even focus on where their dollars are distributed. But a lot of what matters in systemic change, the real nuance is lost when we focus there.

So with Imaginable Futures, we decided to create a systems and impact conversation guide. This is a very loose conversation protocol. It helps partners and us as well to see the changes happening in the systems we work in. It looks a bit different from a typical interview. So the first question is incredibly wide open. It just asks, “What are the changes you’re observing in [short definition of the system that is relevant]?” And some prompts to think about the range of changes.

We actually had folks sometimes take 20 minutes, 30, even 40 minutes, to answer that one question. And the rest of the protocol just prompts and builds on things they talked about. So maybe they gave us a ton about these really visible, tangible changes – policies, resource shifts, leadership changes – well, then we might spend more time and prompt on things like changes in norms and beliefs or power dynamics.

This approach means our participants in the conversations, they’re telling us stories. They’re telling us their story about how change is happening. We’re not defining for them what’s important and what they need to tell us. Rather, they’re defining for us what’s important about how the system is changing. That goes back to that idea of we want information we can’t see ourselves and we want to be challenged in our thinking.

So this was a pretty big choice. It’s very different from highly systematic same information from every person. So Erin, can you tell us a bit about how Imaginable Futures made a decision to go with a conversation guide as the centerpiece of the framework?

Erin Simmons: Absolutely. First of all, we knew we weren’t alone in the effort to rethink traditional impact metrics, so our first step was to take inspiration from those that had gone before – lots of peer funders, grantees, partners, who were experimenting with other ways of gathering data, oral reporting, for example. And we discovered something powerful: that when you create space for intimate conversations, you get insights that you just simply wouldn’t get from traditional metrics.

Traditional measurement often asks people to fit their incredibly complex reality into small, tight, predetermined categories. But systems change, as you know, doesn’t work that way, and so we designed our conversation guide with the wide open question that Jewlya just referenced: “How is the system changing?”

And through the implementation of this approach, we found that we were on to something. We heard from internal colleagues that even though this process was time intensive, it was the best conversation they’d had all year. And from grantees – those of you on the call will hold us accountable to this today – we consistently hear what a gift it is to be able to lift up from the day-to-day work and think about the big picture change that we’re collectively pursuing together.

And the beauty is that we didn’t have to lose the rigor in this choice, but we redefined rigor against the actions that we knew we could take as a result of gathering the data and that our grantees and the broader ecosystem might take. So we start with this sense of shared humanity, interconnection to being in this system together.

So I’d really love to invite the voices of Enyi and Nathalie who are doing this work in context, to hear how this implementation has shifted their own understanding and their grantees’ understanding of the change. So Enyi, I’ll pass it off to you. Would love to hear about an insight that you’ve been able to gain from either our story survey or the conversation guide.

Enyi Okebugwu: Definitely, Erin. Maybe I’ll hone in on our conversation guide. Even if we have regular communications with our partners throughout the ecosystem, having a conversation guide for our systems and impact work is helpful because it helps us walk the line of learning on multiple fronts.

First, the process of finalizing a template that can be used across our partners helps us to gain clarity on key questions we have in the system related to our current strategic priorities.

Secondly, the guide helps us sort of focus in on where the system is today, where there’s energy, where there are critical gaps in the system, and then leaning into these questions through the guide helps us gain clarity on uncharted waters or new priorities in the system, and that can help us inform whether we double down in a particular area or plan new exploratory work that responds directly to field needs and insights.

And finally, having a consistent guide for these conversations helps us gather insights that are both: a) representative of the field – those that validate or complement a strategic assumption we hold, and b) those that are outliers or on the edges of the system, but still useful intelligence for us, and help us interpret those insights in context.

I’ll turn it to you, Nathalie, to walk through your own experience using the tools and the framework in your work in Brazil.

Nathalie Zogbi: Thanks, Enyi. I think Enyi highlighted sort of a learning from the use of the tools and the conversation guide specifically. Maybe I’ll choose to highlight a system-related insight that we got – one of many – from last year, when we sort of first applied the framework in Brazil.

One of our learnings last year was that – and this was from a synthesis of multiple of these conversations – that the at-the-time new federal government that had just been one year into its mandate, that while the new federal government had presented a really incredible opportunity for the system in terms of more democratic participation, we were also seeing an outsized influence – or our partners were seeing an outsized influence – of philanthropy in the education agenda at the federal government, and the sort of the power dynamics going on through that.

The sort of the role that capital played in determining some of the key agendas at the Ministry of Education level was something that we needed to be really mindful of as a player in the system of philanthropy. And so getting a lot of insight into the nuances of those dynamics helped us – that was a really actionable insight to ensure that we, as we plan our work and as we execute our work, we’ve been extra mindful, for example, to make sure that we support – any policy-related work that we do, we’ve been supporting civil society organizations that have ample social participation behind them to ensure real legitimacy of sort of the changes that they’re advocating for and that we are helping to fund. So that’s just one example.

Jewlya Lynn: I love those examples. So in Nathalie’s example, you’re hearing about how making sense of power dynamics, both kind of hidden and more visible, and the way in which financial power is showing up within the system, helps to then make sense of why is change happening the way it is. Where do we need to show up? Who doesn’t have power? How do we balance some of this with different ways of the system being influenced? And leads to very concrete decisions.

And from Enyi you also heard about how the process of even going through this and beginning to be very systematic with the information collected triggers new thinking and creates space to feel challenged and to go down new roads and new directions with strategy.

So I know another change that happened for both of your teams related to how these conversations functioned in your relationships with your partners. So how did you ensure the conversations weren’t just for you, that they were mutually beneficial and not just extractive? And in part, because sometimes these were really long conversations, so they needed to bring mutual value. Nathalie, do you want to go first this time?

Nathalie Zogbi: Yeah, that was a really important point for us going in. We wanted to make extra sure we weren’t being extractive, and that the conversations were mutually beneficial. We weren’t sure if we were going to be able to, but that was our intention, and we made sure to collect feedback from our partners at the end of each process to try to get a sense of how they were experiencing it as well.

And what we found actually, Jewlya, was that the level of sort of trust that we were able to build of sort of more intimate rapport with our partners, of a more sort of much more proximate relationship was enabled, actually through the protocol and the framework. Many of our partners actually said that the questions that we asked them were so helpful in spurring more strategic thinking and inviting them to, as Erin said in the beginning, step away from the day-to-day sort of busyness and sort of fire drills to really thinking strategically and systemically about the systems which we are a part of and they are a part of, that many of them actually took the questions from the conversation guide into their annual planning meeting with their sort of leadership teams.

And so we were, we were really pleased to hear that. I think that was where we really were able to sense value in this type of conversation. Enyi, how about you?

Enyi Okebugwu: So I have so many examples. I’ll try to focus on just one which is really salient, because it happened last week, and this is in response to our story collection efforts, because we had an already existing relationship with one of our partners and an established channel for dialog through the systems and impact conversations.

One of our partners reached out in response to the story survey and essentially said, we do have a really interesting story to share related to a specific state they’re working in, but they wanted to give more nuance and context and also chat live through how their work and their impact lines up with what we’re seeing in the work and the ecosystem across different efforts.

This led to greater transparency and trust building with an already existing relationship with a grantee partner, and open dialog around an emerging concern in a system, in this case, as it relates to state policy opportunities and implications for how our strategy may shift or adapt or not, such as leaning in more on supporting specific types of state level advocacy approaches.

Now we had a lot of these conversations as an organization. We held over 60 with our partners across Brazil, Kenya and the US. That’s a significant amount of information that needed to be analyzed to unearth actionable insights and key examples of progress. A key way we were able to do that efficiently was through using an AI-guided approach, which might seem counterintuitive when a main principle of this work is to capture life stories and insights, so we center with humanity first, and also leverage AI to surface and nuance insights that we may miss as we focus on fully being present in conversation.

Jewlya, wondering if you can walk us through the decision to utilize AI, the advantages it provides, and what are your concerns going into leveraging AI, and at this stage, what are your key takeaways and learnings from the process, and how do you continue to ensure that we’re acknowledging both the opportunities and the shortcomings of these kinds of technologies in evaluation processes?

Jewlya Lynn: So it’s always a little controversial to have a conversation about AI, and particularly when you’re doing work that is very driven by and connected to the voices of those most affected by the system. So in kind of my broader work that I’ve been doing, I’ve been thinking a lot about where, within systemic change work, do we need to use AI to take us to the next level, not to replace humans, but to do things we can’t do, and one of those is to make sense of what’s happening in incredibly complex systems fast enough to use the information before the system moved on.

And in this case, we’re talking about at Imaginable Futures, a small, lean team where learning happens right within the program teams. There isn’t an independent office running all the learning work. And we knew if we took a traditional approach to a giant pile of qualitative data, coding it and analyzing it, it would take months, or it would take a dedicated person, and we would lose momentum. The insights wouldn’t be timely enough to inform our strategic decisions.

And at the same time, we understood AI has a lot of limitations, and we knew we were experimenting. We were particularly concerned about bias in the AI analysis, and actually a pretty big question of, can an AI analysis really work with the complexity that you see when you’re looking at how a system is changing? And this was very dense, dense qualitative information we were dealing with.

So to mitigate these risks, we did a couple things. So we had staff who were conducting the conversations write up debrief notes right after and this kind of structured debrief, just three questions was designed to capture their understanding of key takeaways and how the participant had described the system.

The analyst, which in this first year, was me, I scanned through all the transcripts as well as those notes, and I pulled out what are the keywords, the jargon, the quotes, the ideas, the organizations being named, the policies and bills. And the reason we did that is it was really important to make sure we weren’t asking generic prompts to the AI, but rather encouraging and guiding the AI to look at the content through the language and lens that people were offering up in those discussions.

We also assessed the final AI products that were generated against those original human insights, and were able to map whether certain key themes or patterns had been missed or overstated or taken in the wrong direction by looking at how they lined up with the insights.

So AI really did speed up the analysis. So we had five distinct systems that we analyzed in the first year. We had roughly 300 pages of data, some of them were per analysis. So 1500 pages of data. Instead of spending 60 to 80 hours at least per analysis, the whole process for each one of those processes of analysis and report writing, including reviewing all the transcripts, took about 20 hours for each. This meant we could get all of it done in one month. We could move quickly on using the information and being able to use that report in a system sensing process that rapidly led to adjusting strategies.

So we did walk away from this with a commitment to: Okay. AI is offering us something useful. No question, you lose some of the nuance, but you’re balancing different priorities. Can we move quickly enough in a systemic change setting? Are we getting deep enough information to provide us value? And our goal is to find that balance and keep and maintain it over time. So it helped us go deep without slowing us down too much.

I’m also just a quick side note. I’m not going to talk about platforms. Don’t ask questions about platforms, and the reason is, we use multiple ones last year. We’re using different ones this year, and it’s because AI is developing really fast. Each one has limitations. We do combine them very intentionally so that we overcome the limitations of one with the strengths of another. And there is no perfect model. There’s a lot of great ones out there, and the really you need to take the time to assess if they’re going to match what you need.

Okay, I’m going to get us out of the weeds of the AI, so, Erin, how can organizations better balance this idea of being very action oriented and being able to move quickly with the system, with the long-term horizon of systems change? Kind of what advice would you give about how to balance the messy systems change work today, the rigorous measurement that we want about it and the long-term time horizon of committing to systemic change work?

Erin Simmons: Thanks, Jewlya. I’ll build on your final answer there about AI as a starting point. I think what we learned quickly is that there’s just no one right answer, and being super clear about the how and the why you’ll use the data is the best starting point. And so for us, that came in the context of developing our goals for the impact framework and our principles around what it should look like, and being clear eyed about things like we’re a small organization and it needs to be right-sized to the actual people and the time and the energy – that was an important one. So how and why? Starting there.

I think also the importance of bringing our board along on this journey. I think we’d be remiss if we didn’t acknowledge that that important and critical aspect – that the board had to come with us. They were with us every step of the way, from the design of the goals and the principles to the actual outputs of the framework. And we share those insights, both the how and the what along the way and in regular cadence with them.

I think another important lesson that we learned and are still putting into practice, is that we absolutely have to pilot and experiment. So we need to learn from our partners and grantees how they’re experiencing it. We need to make sure that we are not increasing the burden to them, while also learning for us. And we have to not be afraid to leave behind what isn’t working, which is often the hardest thing of all.

And lastly, I think, you know, another important component of this was being humble in the pursuit – recognizing that there are many friends, many peers, many philanthropic organizations, many community-based organizations who are thinking deeply about these questions too, and so finding explicit ways to invite ourselves into that conversation and into those insights was also critical.

So those are a couple of things that come to mind for me as I think about the big takeaways. There are a breadth of questions in the chat. So we’d just like to invite others to go ahead and enter any questions that you have. Jewlya, as you were guessing, there’s lots of questions related to the AI tool, but also lots of questions related to some of the other tools, like the actual conversation guide, etc. And so we will absolutely review those and be happy to share some of that with you all in follow up.

But I’d like to go ahead and point this question over to Jewlya. So there are some questions in the QA about – you’ve talked a lot about the good here. What are some of the challenges? So Jewlya, if you’ll kick us off with one, and then feel free to pass it over to either Enyi or Nathalie.

Jewlya Lynn: There were a ton of challenges. I mean, I think anytime you’re starting something new, it’s an experiment. We actively talked about it as an experiment. We did a pilot, and then we did an experiment, meaning we recognized, even though we had piloted the tool, the first year was still a big, messy experiment.

I think we learned a number of things. When the teams were doing the conversations entirely themselves, it was a big capacity ask, but also they were learning a lot, and the conversation was really powerful to be in. But there are cleanup steps and next steps after you complete a conversation. And so now some of the teams are bridging. They have a consulting partner who works a lot with them, who joins the conversations and does the kind of leg work, but they often still are in those same sessions, so that they’re learning and partnering alongside. So there’s a process of iteration that’s happening.

Also, we’ll say, the first year out, we tried translating the Portuguese conversations into English, and then analyzing. And well, AI seems to do a pretty good job analyzing in Portuguese for Portuguese outputs. And you know, you can get a good set of findings. It does not know what to do with Portuguese translated into English, because sentence structures and metaphors and other things just confuse the crap out of it. And so it was really important in year two to have a Portuguese speaking researcher who could do that analysis and partner with the AI, rather than relying on a translation step in the middle.

I would love to hear what were some of the challenges. Maybe Nathalie, from your perspective?

Nathalie Zogbi: Yes, I think one first challenge that we faced – maybe this is the one I’ll highlight. A lot of our partners, they actually have been, you know, for many, many years, asked a very different kind of question from funders, right? They have been reporting on traditional KPIs and impact metrics, and so being asked about, being asked to take a more systems-oriented view and reflect about the broader systems, and not necessarily their direct work in relationship to the system, is a new kind of muscle, and many of them, initially, I think, had found it really challenging to to have that sort of to reflect at that level versus their direct work, and the changes that were in relationship to their direct work.

And so it required, you know, some it required multiple conversations. Sometimes we started with an hour and a half conversation and we scheduled another to continue exploring pieces that we didn’t get to. And it required a bit of also changing the prompts and really digging deeper into sort of getting folks to think about changes at that level. So I would just name that challenge. But again, it was a challenge that folks really engaged grappling with, as did we.

So maybe I’m seeing here a question around, how do we prepare partners for the conversation? So is it a requirement in the grant agreement? Do you share the questions in advance, and also another question on, how do we capture the information from the conversation? So maybe I’ll go ahead and answer those.

So we didn’t embed this as a requirement in the grant agreement. But every time we approve a new grant, we kind of signal to our partners that we do also hope to learn from them in ways that don’t feel extractive. And so one conversation per year is something that is kind of sort of the minimum we agreed to, as sort of the means to that learning, and so that we can also be good partners to them in offering, you know, other sort of non-financial supports.

And so we do share the questions in advance of the conversation. That’s an important piece, precisely because it may be the first time that they’re being asked to think about questions such as these. And so we try to send those questions ahead of time, maybe a week ahead of time, and we do invite one to two people of the organization to be a part of the conversation, not much more than that, because having too many voices can also make it harder to go through the questions in depth.

We try when they ask who should be, who from our side, should be in the conversation? We tend to say it would be good. It doesn’t have to be necessarily the CEO or someone from the C-level, but certainly someone who has visibility into multiple parts of the system. And so that naturally tends to be someone like the CEO many times or someone at that level.

And then we do ask to record, and we do record the conversations, and we take notes while we go as well. And so that synthesis – as soon as we finish the conversations, the person responsible for conducting the conversation puts in a quick synthesis of what were some of the key insights that were produced. And then, like Jewlya said, we have that sort of fuller transcript that then is used as well through AI analysis that we feed into our broader process.

Erin Simmons: Thanks, Nathalie. I also see a question related to, “Hey, can you describe your how and why?” And we actually shared a blog on this a couple of weeks, maybe months ago, and so I’ll ask my colleagues to put that into the chat, but just to give a brief overview, the goals that we identified, first and foremost, related to the framework, were:

- To make visible our strategies and the actions that we take aligned to those strategies and the changes that we’re seeing.

- To inform strategic action. So first, make visible. Next, inform it.

- To hold ourselves accountable, and that meant to our values, our partners, our board and the broader community and field.

- And fourth, and important to us, as you heard from both Enyi and Nathalie, was to inspire a broader conversation, really, and share our insights back to the field in ways that could support and change and add to and create generative dialog with all of you.

And the principles that we identified, they’re really specific to us as an organization, but they work and we find that even, you know, three, four years in, they’re still holding for us. So that it be:

- Action oriented, not something where we gather a bunch of data and report to think about

- That it surfaces our thinking, makes clear our assumptions about change

- That it’s authentic to us and really represents who we are and how we show up in the field, so it doesn’t create a whole new personality for us in the context of gathering information and data

- Embraces flexibility, as you heard from Jewlya, we are an emergent organization. Change is regular. Pivots are regular.

- And then lastly, that it redefined rigor in our own context, still rigorous, but redefined it for us and how we were using the information.

So I think that’s actually a perfect segue to pivot to Jewlya to share a little bit about – there are lots of questions in the chat around rigor and different types of traditional measurement. So I’ll ask Jewlya to head there.

Jewlya Lynn: There are a ton of questions, so I probably can’t respond to all of it, but I see a bit of a theme. So this is not traditional impact evaluation. We did not have a set of indicators that we were trying to get data in response to. We had a set of big questions about what was happening in the system, and that protocol’s intentional, wide open storytelling approach meant that had we come in saying we want to know A, B, C and D, we want to measure how change is happening over time on these specific things, we would lose some of that.

And if it’s really critical to capture that level of “there’s a very specific part of the system we’re trying to change,” I think that’s a separate and really important and additive piece. But what we were doing here is being careful not to assume we knew what mattered in the system, and instead asking people coming from very different perspectives about how they understood how the system was changing.

There were a couple of different questions that are essentially, “Well, how do you validate those findings? How do you know what someone is saying is true?” First off, it’s perception data, so we have to recognize that. Yes, we can feel more confident when multiple people have said the same thing. But also, everybody has a slightly different lens into the system, and we’re going to get some things that only one voice says. Do we want to reject it because it was one voice, or do we want to weigh how seriously it’s going to influence our changes if we don’t have time to follow up? I think that’s more what we would do.

But I have to say, one of the things that was really fascinating is about six or seven conversations in, we mostly were getting information we had already gotten before. So we really didn’t need 20 conversations, because we weren’t asking people about their own work and their own outcomes. We were asking them to describe a system they were all working in. And so the nuance and the new information really came from this not being a conversation they normally had with us, as opposed to it being really nitty gritty and specific information that only they had access to.

And this protocol, it actually worked so well that I’ve since used a very similar approach in a large 10-year systems change study, and found that you really can, if you want to go deeper, you can then investigate key kind of causal links that exist within these larger stories and begin to unpack where and why and how change happened in a much more rigorous way. I think of what we get from this as a scaffolding of a systems change story, and there’s always room to go deeper.

I would encourage for a lot of these questions you guys are asking that get at rigor and quality, go to the Inclusive Rigor framework, and we can send some follow up resources. But this is amazing work happening globally, with folks in many different areas of practice who are trying to rethink and redefine rigor using a participatory and action-oriented lens and really honoring the inherent complexity of the work we’re all doing together in the systems change spaces. Thanks.

Erin Simmons: Thanks, Jewlya. Enyi, I’d love to invite you in to answer two questions. The first is, can you talk about an insight that actually led you to a pivot in the work that you’re doing? And maybe you’ll think about that one. The second is, how do you share these insights with grantees?

Enyi Okebugwu: The first question has multiple responses. I’ll try to stick to one. The focus of our two years of systems and insights conversation and impact conversations have centered on the early childhood field, and specifically childcare. One of the insights that emerged last year, and sort of was deepened this year, as we’re in the context of a very charged political climate in the US, is where do we focus our energy? Is there energy in the system around protecting the good in the system today, or is there energy in the system around exploring like what could change, what could be new in the system, looking on a 5, 10, 15 year horizon?

And we saw the insight that really stood out to us as a team, was there’s everyone thinking about having impact around protecting what is today, and there’s still emerging space, but not a lot of efforts around synthesizing, catalyzing space for reimagining what the future could look like, particularly in the childcare system. So a pivot for us is, can we help create that space? So that’s something that we’re in early stages of exploring today, of how can we catalyze reimagining the childcare system for the next decade plus to come?

And then to answer your second question, I think we’re still trying to figure out what is the best way to share insights with the field. We take the insights from our conversations and sort of scrub them down for privacy purposes and share what we call our systems and impact conversation reports with those that we did have the conversations with, so they can leverage them in similar ways to how we’re leveraging them in our work and our strategy purposes.

But one way we’re thinking about how we can deepen that impact is who do we share with beyond those that we talked to for the benefit of the field, while still honoring the intimacy of the conversation that we’re having. So I’ll pause there, and I’ll kick it back to you, Erin, to wrap this up a little bit.

Erin Simmons: Thanks, Enyi. Let me go over to Nathalie one more time for a similar subset of questions, but connecting how we bring partners together in this?

Nathalie Zogbi: Sure. Yeah, I see here a question from Vanessa around. She says, “It sounds like all the conversations are between IF and each grantee partner, how do you encourage learning or collaboration across your grantee partners? And if so, have you seen the benefits?” That’s a great question. We’ve actually been prototyping and testing different ways to do that.

So one example in Brazil – in our Brazil work, we’ve been gathering what we call a system sensing roundtable with six grantees over the past, actually, two and a half years. So this has been a sort of consistent initiative where six grantees that work in different levels of the system, from sort of community-based interventions to more policy level, have been meeting sort of almost on a monthly basis with a few week-long immersions every year to really go deep into shared monitoring, evaluation and learning practices, mostly rooted in participatory monitoring and evaluation practices.

And so that kind of cross – that learning across organizations in the field has been extremely rich. I think it has been rich from the perspective of helping everyone to better understand dynamics in the system, but also helping to strengthen each of their interventions and tactics by learning from one another, by understanding that many of the challenges that they have faced are similar across and being able to identify common patterns.

And so we’d be happy to share more on that initiative, but these are still experiments and not really incorporated into sort of our main firm-wide system and impact framework. So we continue, we continue evolving and and like Enyi said, I think we still have a lot regarding how we share these insights back into the field in ways that both honor the sort of the privacy, the in-depth conversations that sometimes reveal things that might not want to be named with sort of having that knowledge and level and those insights live more broadly and be accessible to the system. So more to come on how we evolve on that front.

Erin Simmons: Thank you. Looking at the time we’ve got just one question left, and I’ll turn it back to each of our panelists today. I’d love for each of you to share just one piece of advice, or your biggest takeaway. Enyi?

Enyi Okebugwu: My biggest piece of advice: learning is a nonlinear, constant journey. So we are still, you know, adjusting by the week, how we undertake our learning work. So I’ll pause there and kick it to Nathalie.

Nathalie Zogbi: Yeah, I think similarly, even though I feel, you know, I feel it’s a tremendous responsibility to be presenting our systems and impact framework to, you know, amazing colleagues in the field. And it’s, you know, sometimes presenting something like this makes it seem like we think it’s ready to be presented, but truly, it’s a constant work in progress, and it’s like Enyi said, evolves by the day, and there’s still so much we don’t know.

And so I would just, you know, both thank people who are on this call for sometimes even being inspirations that have helped us here without knowing, but also, just like put us really right by the side of everyone who’s listening in and saying, you know, we look forward to continue learning together and exchanging and please do reach out if you have ideas on how we can collaborate. I’ll pass it to Jewlya for hers.

Jewlya Lynn: Okay, so I guess my biggest piece of advice is don’t replicate this framework, not because it hasn’t been a very effective tool for Imaginable Futures. But because the thing that really, I think, was most powerful here was the process this team took to figure out what they needed, and within that process, the real commitment to looking at the system first, rather than centering everything on their own work and sitting with and being comfortable with the uncertainty.

They didn’t go into this trying to design a complete monitoring, learning and evaluation plan, but rather a learning process that was good enough to be worth experimenting with, and then they’ve continued to adapt it. So that’s what I think is worth replicating, is that journey that they’ve gone down to wherever it leads you. Erin?

Erin Simmons: Thank you so much, all three of you. I think I’ll close with my final piece of advice, which is just get some friends who can tell it to you straight. I think that’s been the biggest gift of this is having partners who can be on that journey with us, who are willing to tell us when we got it wrong and also when we get it right, and we just invite this community as well to be along on that journey with us.

What a wonderful conversation we’ve had today. On our website, we have a special section around what we’re learning. We do try to share our transparent, ongoing work-in-progress, “good enough” process there across a host of dimensions in our work, and we love to hear from you. We love to hear what you’re doing that can make us better. We love to hear what you’re trying out, what’s worked, what hasn’t. So continue to do that.

And most importantly, to our partners, thank you for being willing to share your transparent selves. We feel so grateful to be in this with you. And thank you so much to all of you who joined today and those that will be watching in follow up for being part of this conversation, for your deep, engaging questions, and we hope to see you at the next fireside chat. Thank you so much for all of your time today, and thanks so much to Enyi, Jewlya and Nathalie.

Read the fireside chat recap blog here.